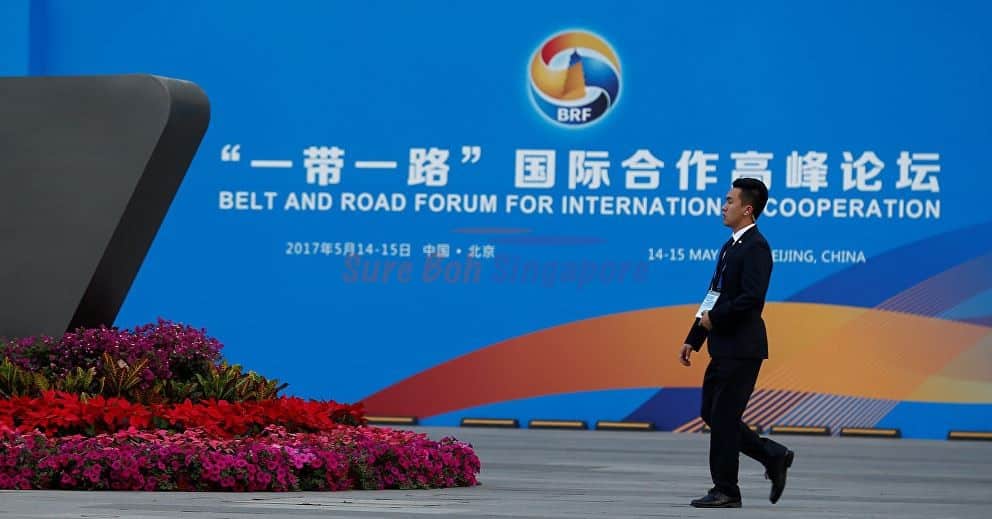

Beijing might have put on a spectacular light show in conjunction with the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation, which concluded on Monday, but it was China’s political ambitions that shone the brightest.

At a time when United States’ global leadership is found wanting with its mercurial president seemingly intent on turning America away from multilateral engagements, and the European Union distracted by its Brexit woes, China has a unique opportunity to be a champion of free trade and globalisation.

The Belt and Road Initiative makes a strong statement — and case — for China’s growing leadership credentials. This ambitious project, which brings together 65 countries across Africa, Asia and Europe, bridges geographical, political and cultural divides to foster economic growth, uplift communities and enhance people-to-people understanding.

The active participation of 29 heads of government at the forum, along with a long list of special envoys and senior representatives from the participating countries, speak of the broad support for the new initiative, which is inextricably linked to Chinese President Xi Jinping’s leadership and legacy.

But while accolades for China’s efforts to finance infrastructure development are well deserved, the celebrations may be premature.

In fact, the Belt and Road Initiative presents a stern test for China. Notwithstanding China’s deep pockets, success is by no means guaranteed.

ALIGNING INTERESTS

For starters, China has to manage expectations and match Beijing’s interests with those of the initiative’s participants.

A recent study by the Asian Development Bank indicates that developing Asia would need to invest US$26 trillion (S$36 trillion) from 2016 to 2030 to fulfil its infrastructure needs.

However, most of these pressing demands are internally driven, including power generation, water and sanitation, and transport. It would be a boon if Chinese resources are used to fund these under-financed projects, but these may not necessarily serve China’s strategic interests.

Second, China has pledged US$124 billion ($174 billion) to underwrite infrastructure projects under the Belt and Road Initiative banner. That is a vast sum, even by Chinese standards.

But the perception that China is bankrolling and funding the Belt and Road Initiative projects is not entirely accurate. For example, while the Jakarta-Bandung rail project is listed as part of the Belt and Road Initiative, Indonesia holds a 60 per cent stake in the US$5.5 billion project.

Likewise, the Laotian government took out a loan to cover its 30 per cent equity of the US$5.8 billion Kunming-Vientiane rail link.

The recipients bear significant risks in the viability of the projects and are also responsible for the servicing of the debts. Therefore, Belt and Road Initiative projects must first and foremost make financial and economic sense to the host country and not merely serve Chinese interests. Would China be able to separate its self-anointed role as international financier from its strategic interests?

The Belt and Road Initiative is a bold strategy to connect the world to China. If this vision comes to fruition, it would create a vast network of land and maritime connectivity where “all roads lead to Beijing”, enhancing China’s centrality and cementing its position as an indispensable node in international trade and finance.

As alarming as this proposition may sound to some, especially Western ears, the spread of Chinese influence and power is not news to the Association of South-east Asian Nations (ASEAN).

A recent survey by the Iseas-Yusof Ishak Institute showed that nearly 74 per cent of the South-east Asian respondents identified China as the most influential country in the region.

What does concern ASEAN is the lack of reciprocity in opening China to the world.

The Belt and Road Initiative will give China a substantive economic and political lift in the participating countries, but this novel idea would fall short of its “win-win” objective unless China re-examines its trade strategy.

Of particular interest to the region is ASEAN’s trade deficit with China, which has ballooned from US$6 billion in 2010 to US$77 billion in 2015. Nine out of 10 ASEAN states run a trade deficit with China.

UNBALANCED RELATIONSHIP

The skewed trade relations may have unintended consequences. The Tanaka riots of 1974 provide a cautionary tale for China. In the 1970s, Japan invested heavily in South-east Asia but neglected to take into consideration the needs and interests of the host countries.

Emotions against Japan’s neo-imperialism came to a head in January 1974 when mass riots broke out in Jakarta during then-Japanese prime minister Kakuei Tanaka’s visit to Indonesia. Japan subsequently mended fences by enunciating the Fukuda Doctrine and pledged to conduct “heart-to-heart” relations with South-east Asia.

China should not fall into the trap of being a victim of its own success. While ASEAN wholeheartedly welcomes the Belt and Road Initiative and the closer economic relations it brings, China should not take the region for granted.

Economic success is tenuous unless it is supplemented by political cooperation and strategic trust. As ASEAN appears to grow ever closer to China’s economic orbit, what assurances can China offer that it would be hegemonic and benign in equal measure?

President Xi has offered the region and the world a vision for closer economic, political and social relations — broad ideas that are consistent with ASEAN’s approach to regional peace and prosperity.

However, the devil is in the details and it is the implementation of these ideals that would test China and ASEAN’s friendship.

This is a test that ASEAN and China would want to pass with flying colours, an outcome that will ultimately hinge on the commercial viability of the projects.

Prestigious projects built on shaky economic foundations will surely bury the recipients of Chinese largesse in a mountain of debt. This might further exacerbate the existing imbalance in this important bilateral relationship.

China’s former paramount leader Deng Xiaoping has the enduring legacy of opening China to the world and facilitating China’s transition to a market economy.

By literally bringing China to the world through the Belt and Road Initiative, President Xi could consolidate China’s position among the world’s leading powers and — if successful — have a significant impact on how the world sees China.